Current treatments for HA

Bleeding prophylaxis

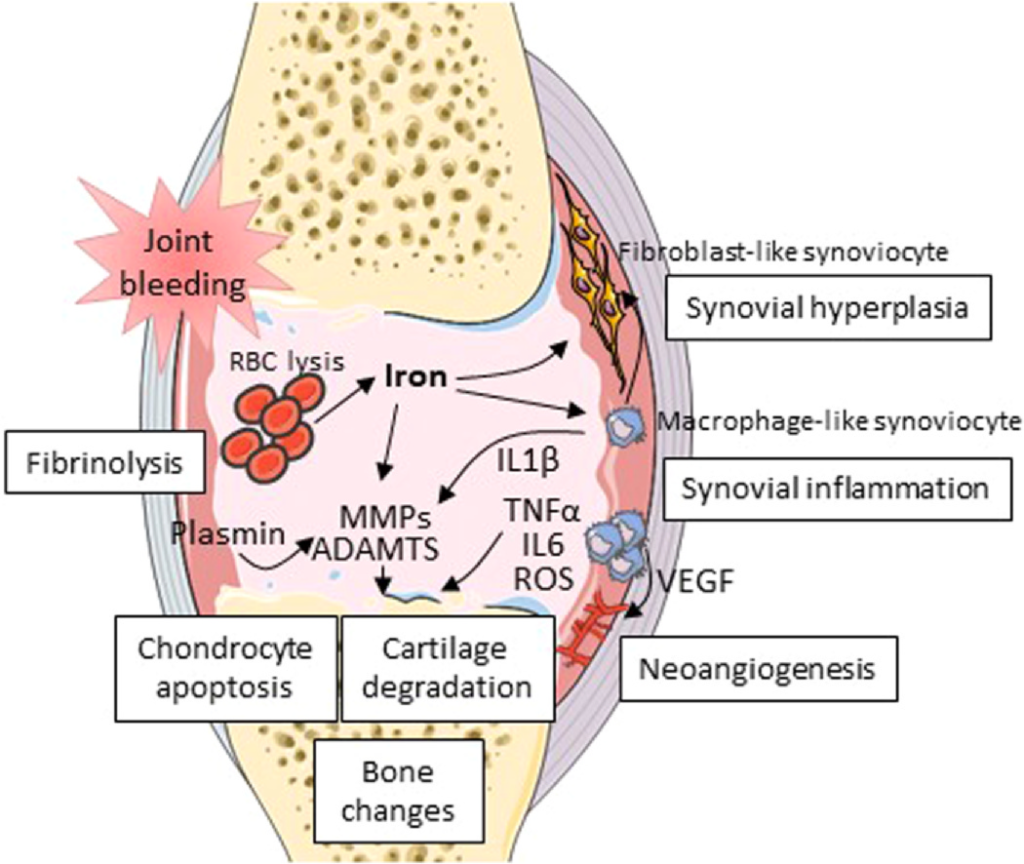

The ideal treatment for HA should be preventive. Indeed, the implementation for prophylactic coagulation factor replacement therapy for more than twenty years has shown a positive effect on the reduction in the number of joint bleedings and on HA development, particularly when applied prior to the age of four. 19,20 In addition, a decline in the proportion of total knee replacement surgeries was demonstrated in a 3-decade cohort retrospective study, likely reflecting the benefit of prophylaxis.21 But other studies show that minor and moderate hemophiliacs experience a higher Fig. 1 Main mechanisms involved in hemophilic arthropathy. ADAMTS: A disintegrin and metalloproteinase with thrombospondin motifs; IL: interleukin; MMP: metalloproteinase; RBC: red blood cells; ROS: reactive oxygen species; TNF: tumor necrosis factor; VEGF: vascular endothelial growth factor. 2 A. Théron et al. / Osteoarthritis and Cartilage xxx (xxxx) xxx–xxx risk of developing joint pathologies than the general population, which might be related to asymptomatic intra-articular bleedings.22,23 Indeed, some studies have reported ankle joint damage in patients with moderate to minor hemophilia, in relation with microtraumas consecutive to physical activities.24,25 Current prophylaxis therefore reduces the occurrence and duration of hemarthroses, but the impact of nano- and micro-bleedings on HA is still under debate.26

Local treatments

To date, there are only palliative treatments for HA, primarily for pain relief using analgesics. In addition, local treatments such as infiltration of corticosteroids or hyaluronic acid can be prescribed to patients. In the event of predominant synovitis, surgical, chemical or radiation-induced synoviectomy is an option that can improve and slow-down the progression of joint amage.27 Recent studies have reported promising results of ankle joint distraction with clinical and structural improvement in hemophilia patients.28,29 This technique has proved its interest in other rheumatic diseases such as OA, with clinical and radiological improvement of the joints.30 External fixators are fairly well tolerated during the 10-weeks treatment period, although this is an invasive technique with an increased risk in hemophilia patients.28 To date, there is no data on patients treated with inhibitors, who are at greater risk of bleeding during invasive procedures and more affected by arthropathy. 31,32 Moreover, this technique cannot be applied to all the joints that may be affected in hemophilia patients.30 Finally, in case of dramatic damage to cartilage and/or bone, surgeries for arthrodesis or prosthetic replacement of the joint are indicated.33

Targeted treatments

In hemophilia, dysregulated fibrinolysis has been associated to HA occurrence. Inhibiting the fibrinolytic system has been therefore evaluated as a therapeutic option. As a result, intra-articular injection of small interfering RNA directed towards protease-activated receptors 1-4 or anti-plasmin antibodies have been shown to attenuate synovitis and plasmin-induced cartilage damage in hemophilic mice.34,35 A number of anti-inflammatory treatments have been tested in vitro and/or in vivo to inhibit synovial inflammation in HA models. Conventional anti-inflammatory drugs have failed to demonstrate a long-term effect in preventing HA.36 However, the administration of IL4, IL10 or IL4-IL10 fusion protein has been reported to attenuate bloodinduced cartilage damage in hemophilic mice although no clear impact on synovial inflammation was observed.13,37,38 By contrast, the use of anti-IL6R antibodies as an adjunct to FVIII therapy has been described to reduce synovial hyperplasia and macrophage infiltration and protect from HA.39 Similarly, a treatment with anti-TNFα antibodies was shown to attenuate macrophage accumulation in the synovium of hemophilic mice and to reduce synovial thickness and vascularity in patients with HA.40

Iron, the major trigger of synovial inflammation, is another potential target in HA. The use of iron chelators has therefore been

tested with the final aim of reducing cartilage degradation but in vivo studies have reported disappointing results.2,41,42

Finally, other studies have targeted bone remodeling in order to slow down the harmful consequences of joint damage on the subchondral bone as described in HA. Bisphosphonates, the main therapy for bone remodeling in case of osteoporosis, have been

shown to improve the bone mineral density and to reduce bone resorption in patients with hemophilia.43

Currently, none of the proposed treatments has entered into the clinics highlighting an urgent need for new therapeutics for the

management of HA in hemophilia patients. In this particular disease where unpredictable repeated intra-articular micro- and nanobleedings lead to irreversible joint lesions, the availability of treatments that could prevent or slow-down blood-induced alterations would be of high interest for the community. One potential innovative strategy would be to rely on cell therapeutics, in particular using MSCs that are under clinical evaluation for the treatment of more prevalent rheumatic diseases such as RA and OA.